Humans have always taken pride in their remarkable achievements, from the intricate designs of particle accelerators to the creative realms of poetry and the playful universe of Pokémon. These accomplishments are all made possible by a trait we hold in high regard: intelligence. However, defining intelligence is not as straightforward as it might seem. While we often think of it as a trait like height or strength, its true nature is much more complex and multifaceted.

In essence, intelligence is a mechanism for solving problems, particularly those related to survival—such as finding food and shelter, competing for mates, and evading predators. It encompasses a range of abilities, including knowledge acquisition, learning, creativity, strategic thinking, and critical analysis. These abilities manifest in various behaviors, from instinctual reactions to sophisticated learning processes and even a degree of awareness. However, scientists often disagree on where intelligence begins and what should be considered intelligent behavior.

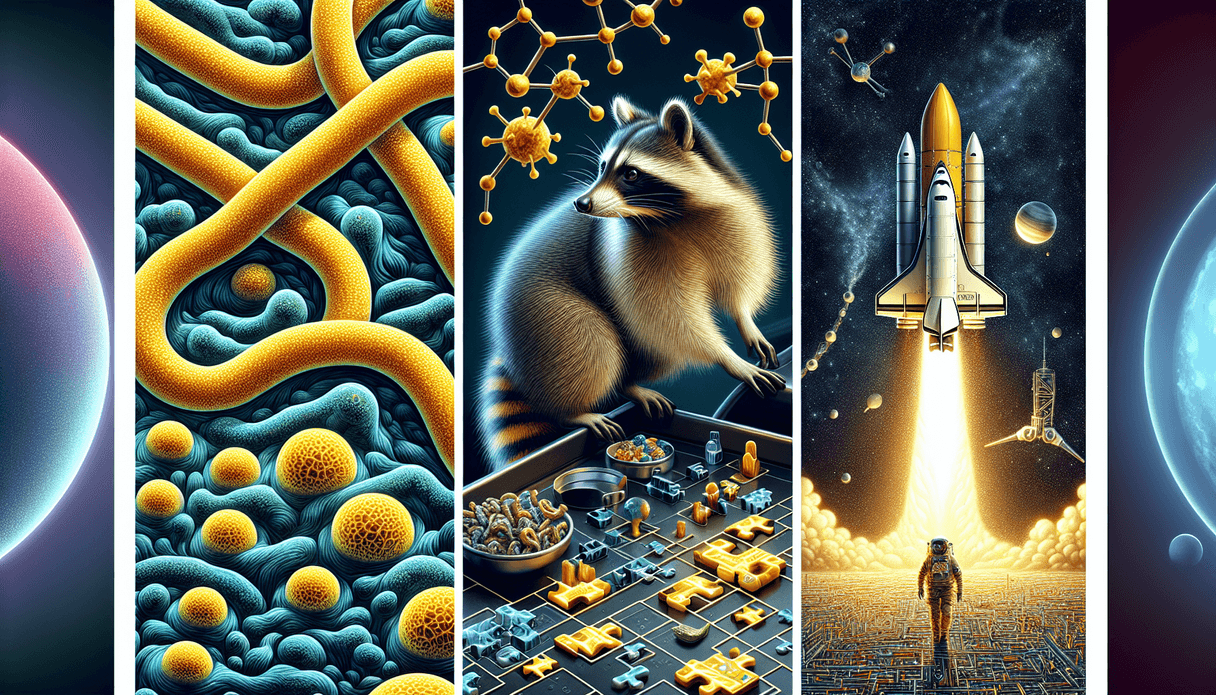

To simplify, we can think of intelligence as a flexible set of skills—a toolbox. Let's explore the different tools in this intelligence toolbox and how they enable living beings, from slime molds to humans, to navigate and solve the challenges they face.

Basic Tools: Gathering Information, Memory, and Learning

The most fundamental tools in the intelligence toolbox are the abilities to gather information, store it, and use it to learn. Information about the world is gathered through senses such as vision, sound, smell, touch, and taste, allowing organisms to navigate and react to their environment. Additionally, living beings need to monitor their internal states, such as hunger and fatigue, to make appropriate decisions.

Information Gathering

Information is the foundation of action for all living things. Without it, organisms would be at the mercy of their surroundings, unable to react appropriately or flexibly. For example, the acellular slime mold, a single large slimy cell, exhibits behavior similar to that of an animal with a simple brain. When placed in a maze with food at one end, the slime mold explores its surroundings and marks its path with slime trails, effectively creating a memory map. By avoiding these marked pathways, the slime mold efficiently finds its way to the food, demonstrating a form of problem-solving that, while hardwired, provides a significant advantage.

Memory

Memory, the ability to save and recall information, is the second essential tool. It allows organisms to avoid starting from scratch each time they encounter something relevant. Memories can pertain to events, places, associations, and behaviors such as hunting or foraging methods. For instance, bees have been trained to move colored balls into goalposts for a sugar reward. Over time, they became more efficient, choosing the ball closest to the goal even if it was a different color from the one they were trained with. This adaptability showcases their ability to learn and improve their behavior based on past experiences.

Learning

Learning is the process of assembling a sequence of thoughts or actions into repeatable behaviors that can be varied and adapted. This tool enables seemingly simple creatures to act in surprisingly intelligent ways. For example, raccoons, known for their love of human food, have demonstrated remarkable problem-solving skills. In a study, raccoons were given boxes secured with various locks, such as latches, bolts, plugs, and push bars. They quickly figured out how to open each box and remembered the solutions even a year later.

Advanced Tools: Creativity, Physical Tools, and Planning

As we move up the complexity ladder, more sophisticated tools come into play, allowing animals to solve a wider range of problems.

Creativity

Creativity, often described as mental duct tape, involves producing something new and valuable from seemingly unrelated elements. It means making novel connections between inputs, memories, and skills to devise unique solutions. In another raccoon study, researchers showed the animals that dropping pebbles into a water tank could raise the water level enough to reach a marshmallow floating at the top. One raccoon, however, came up with a more efficient solution: it tipped the tub over. This creative approach highlights the raccoon's ability to think outside the box.

Physical Tools

Using physical tools is another advanced aspect of intelligence. Primates, for example, use sticks to fish for termites in trees, while some octopuses assemble collected coconut shells around themselves as portable armor to hide from predators. This ability to repurpose objects for specific tasks demonstrates a high level of problem-solving and adaptability.

Planning

Planning involves considering the activities required to achieve a desired goal and organizing them into a coherent plan. This tool requires assessing unforeseen circumstances and new possibilities to determine whether they align with the plan. An example of this behavior is hoarding food for future consumption, a common instinctive behavior in squirrels. Despite its instinctive nature, squirrels use advanced thinking skills to make the best decisions. They examine each nut, weighing the time and effort needed to hide it against its benefits. Damaged or low-fat nuts are eaten immediately, while those that need to ripen are stored. Squirrels also engage in deceptive behavior, pretending to bury nuts to distract rivals from their real caches. This level of strategizing requires an awareness of others' intentions and desires.

The Human Intelligence Toolbox: Culture and Collaboration

Humans have developed an exceptionally diverse intelligence toolbox, which has been further enhanced by the addition of culture. Culture allows us to share knowledge across generations and collaborate on complex projects that no single individual could accomplish alone. This collective intelligence has enabled us to shape the planet to our liking, creating both remarkable advancements and new challenges.

Collective Intelligence

No single person could build a space rocket or a particle accelerator on their own. However, through collaboration and the sharing of knowledge, humans have achieved these feats and more. This collective intelligence has allowed us to tackle problems beyond the capabilities of any individual, leading to advancements in science, technology, and society.

New Challenges

While our intelligence has brought about incredible progress, it has also created new problems, such as climate change and antibiotic resistance. Addressing these issues requires us to look beyond short-term survival and consider the long-term impact of our actions. We have the tools to solve these challenges, but we must use them wisely and collaboratively.

Conclusion

Intelligence is not a single, clear-cut trait but rather a flexible set of skills—a toolbox that enables living beings to navigate and solve the challenges they face. From the basic tools of information gathering, memory, and learning to the advanced tools of creativity, physical tools, and planning, intelligence manifests in a variety of behaviors across different species.

Humans have taken this toolbox to new heights, adding culture and collaboration to our repertoire. This collective intelligence has allowed us to achieve remarkable feats and address complex problems. However, it also presents new challenges that require us to think beyond immediate survival and consider the future.

By understanding and utilizing the full range of tools in our intelligence toolbox, we can continue to innovate, solve problems, and create a better world for future generations. So, let's unlock the potential of our intelligence toolbox and tackle the challenges ahead with creativity, collaboration, and foresight.